WHY IS IT ESSENTIAL TO KEEP THE PAP?

BECAUSE THEY’RE WORTH IT.1 in 5 women with cervical cancer were missed by screening with HPV-Alone.*1 Pap + HPV (co-testing) empowers you to do everything you can to protect the health of your patients.

WHY IS IT ESSENTIAL TO KEEP THE PAP?

BECAUSE THEY’RE WORTH IT.1 in 5 women with cervical cancer were missed by screening with HPV-Alone.1,2* Pap + HPV (co-testing) empowers you to do everything you can to protect the health of your patients.

Leading cervical cancer screening

Hologic’s Offerings

Our specialized suite of testing tools lead the way in creating a brighter future for women’s healthcare.

ThinPrep® Pap Test

Aptima® HPV assay

Aptima® HPV 16/18/45 genotype assay

Know the facts

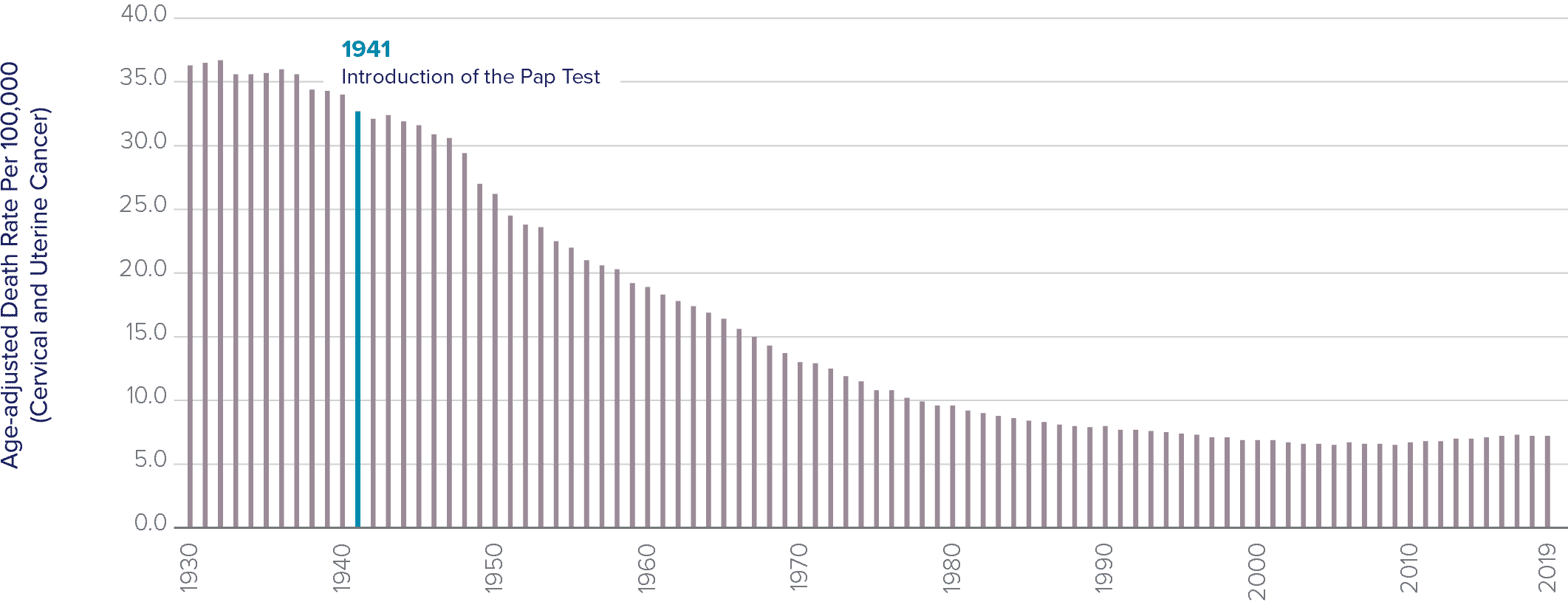

The Pap test has been the most successful cancer screening program in history.5

The rate of cervical cancer, which was a leading cause of death among women, has fallen by more than 70 percent since the Pap test was introduced over 80 years ago.6 Previously, cervical cancer was the leading cause of cancer death in women, but now it is the fifteenth most frequent.

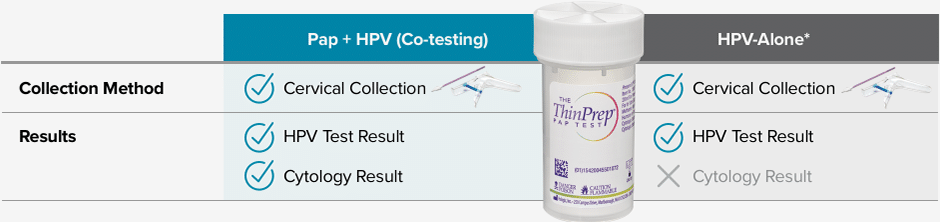

The difference is in the results – with HPV-Alone*, you will receive less information with the same collection.

Samples may be collected in an FDA-approved liquid-based cytology medium such as the ThinPrep® Pap Test.

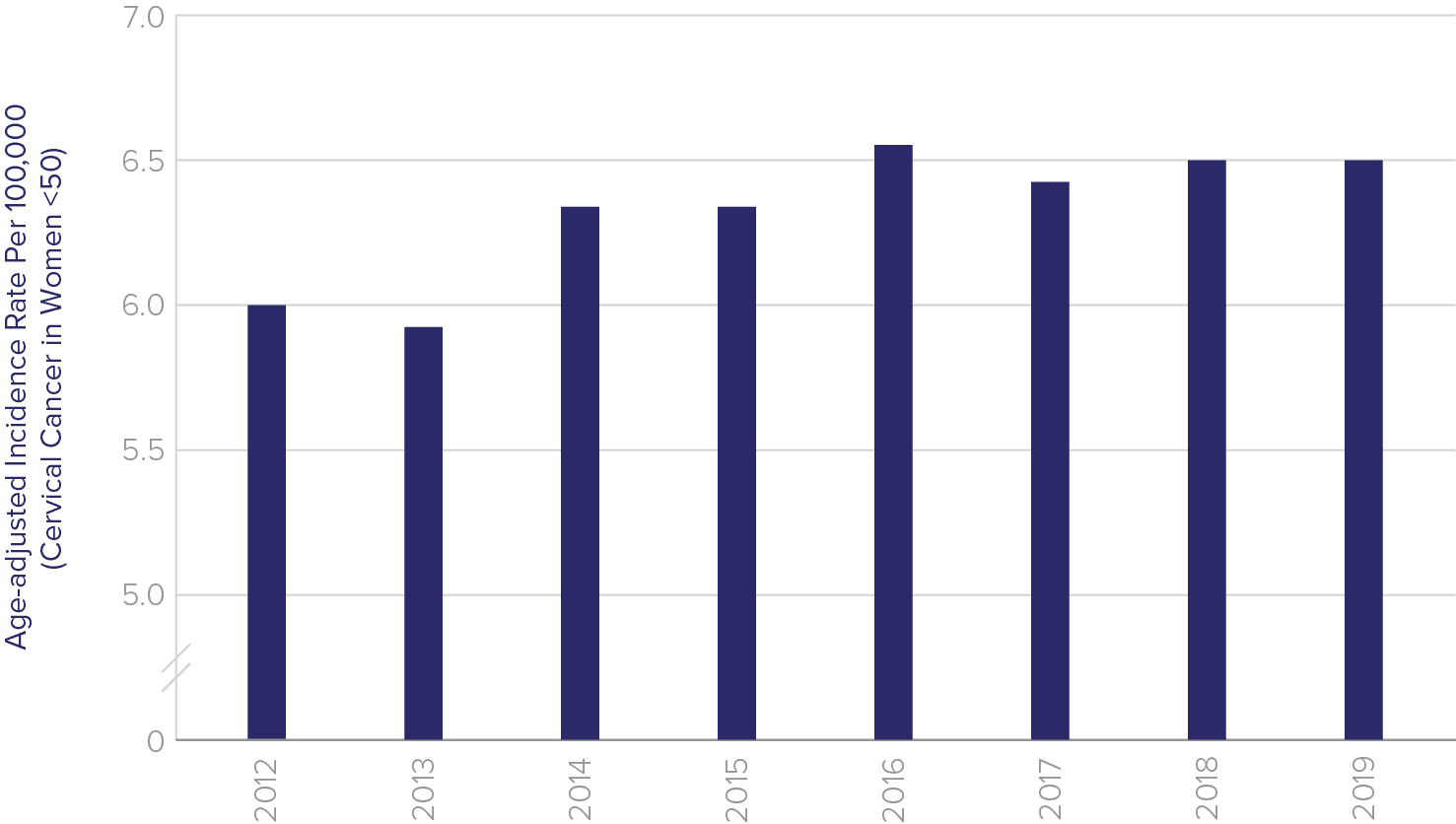

Is this the right time to make more drastic changes to screening?

“At no point in the publications describing the new guidelines [2012 consensus guidelines] it is acknowledged that we are now recommending more cancer and more death from cancer than the previously recommended 3-year cotesting provides, and that we are doing so presumably for the purpose of avoiding a cervical treatment that is not associated with detectable increased mortality.”

Choose Pap + HPV

Recent publications representative of US clinical practice showed

Pap + HPV (co-testing) misses the fewest cancers/precursors to cancer:

Recent publications representative of US clinical practice show Pap + HPV (co-testing) misses the fewest cancers/precursors to cancer:

Don’t sacrifice

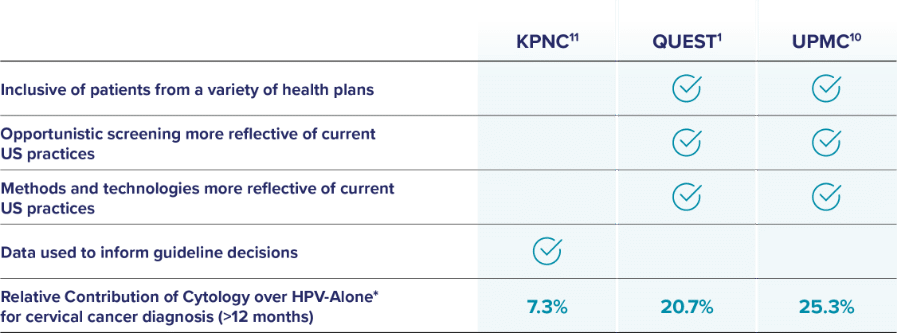

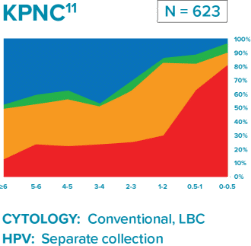

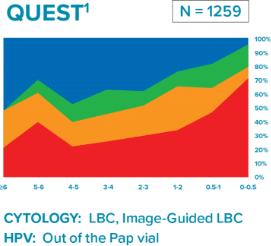

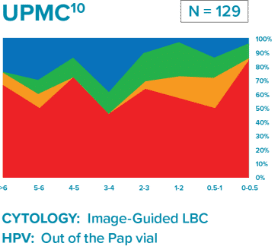

Comparison of three longitudinal co-testing studies.

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC): Regional laboratory and Integrated Delivery Network

Quest Diagnostics: National reference laboratory

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC): Large academic medical center

“Liquid based cytology (LBC) enhanced co-testing detection of cervical cancer … to a greater extent than previously reported with conventional Pap smear and HPV co-testing.”

Disparities in cervical cancer care fall along racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines

Screening rates for cervical cancer are low and continue to decline because many women do not adhere to the recommended guidelines. Results from the Rochester Epidemiology Project reveal the following statistics:11

For 21 – 29-year-olds

Only

47%

of eligible women were up to date with the Pap test

For 30 – 65-year-olds

Only

65%

of eligible women were up to date with Pap or Pap-HPV co-test

Diverse populations are underrepresented in the data

The ACOG, ASCCP and SGO are aligned with the USPSTF 2018 guidelines, offering all three screening modalities.

The ASCCP acknowledged

this limitation stating:

“The ASCCP recognizes the benefits and risks of primary HPV cervical cancer screening while acknowledging the barriers to widespread adoption, including implementation issues, the impact of limited HPV vaccination in the United States, and inclusion of populations who may not be well represented on primary HPV screening trials, such as underrepresented minorities.”18

The ASCCP released a publication

aligned with the USPSTF 2018 guidelines:

“The USPSTF recommendations include all screening modalities, providing flexibility that may benefit those who are marginalized, underinsured, or experiencing inequity and health disparities.”

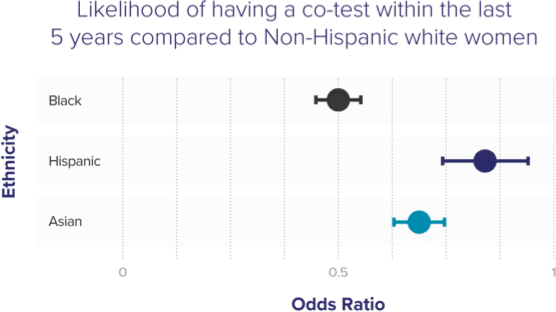

Black, Hispanic and Asian women are less likely to be up to date with screenings than white women17

Black, Hispanic & Asian women less likely to be up to date with screening than white women

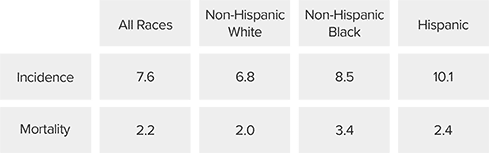

Cervical Cancer Incidence and Mortality

Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States than previously thought, particularly in Black women. In fact, mortality rates in Black women in the US equal or exceed those in many African countries that have organized screening programs.19

2019 cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates (per 100,000)7

Black women in the US die from cervical cancer more than

2x

the rate of white women19

Hispanic women are

30%

more likely to die from cervical cancer, compared to white women20

Reducing cervical cancer incidence requires a comprehensive strategy

Such a strategy will include screening options that take into account disparities that underserved women face. This strategy should focus on reducing preventive screening gaps by:

Implementing provider and patient education

Providing access to vaccinations

Offering the Pap + HPV together (co-testing)

Learn more about Hologic’s commitment to improving health equality.

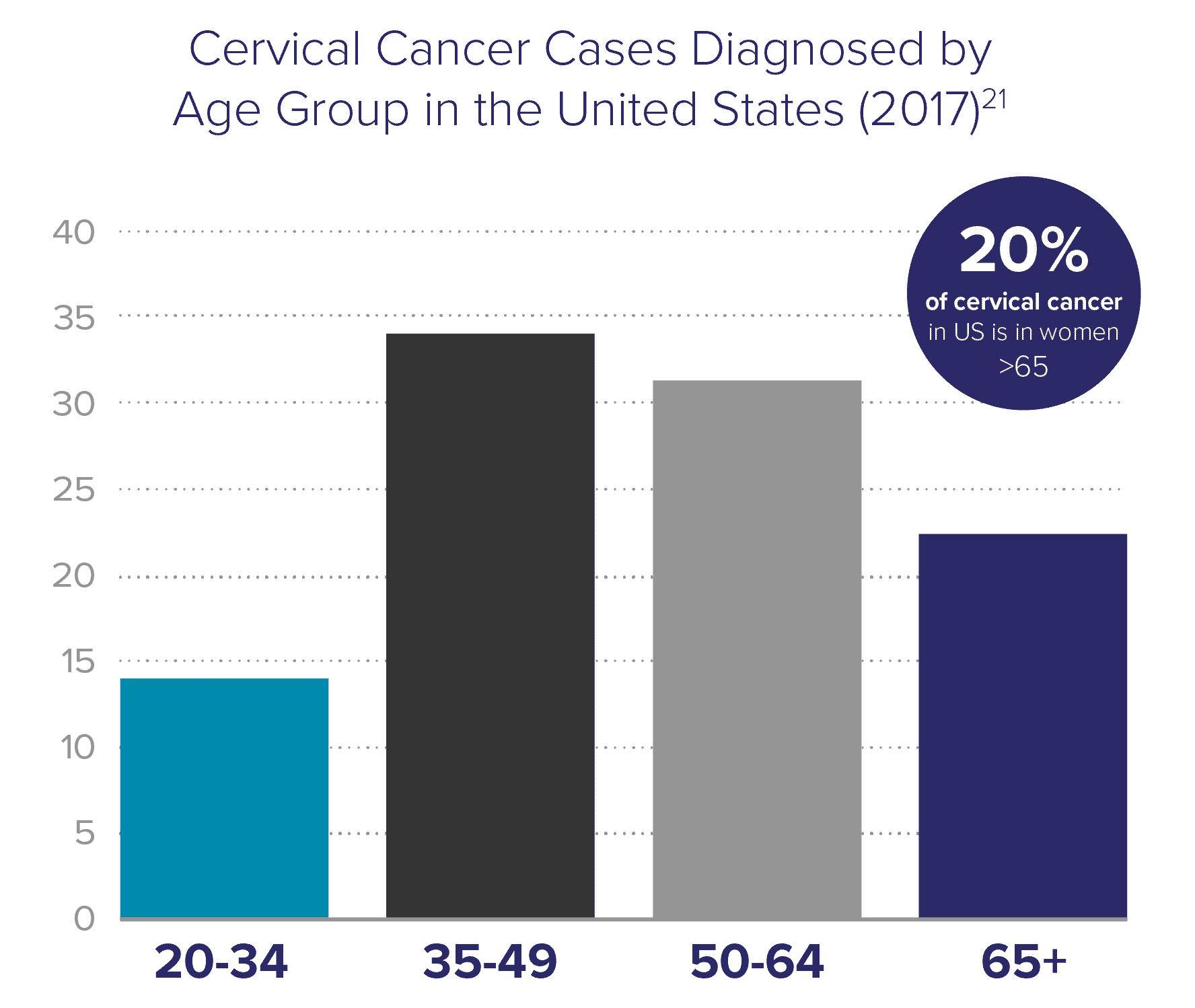

Cervical cancer is not only a disease of younger women

Current screening guidelines state that a patient may exit screening after the age of 65 if she has had a history of negative screening results. However, these guidelines do not adequately address that women are living longer – the average life expectancy in the US is about 20 years beyond 65. Research shows that women over 65 years old account for 20% of cervical cancer instances in the US. This is especially problematic because elderly women are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancer.

Corrected cervical cancer rate in older Black women is 53/100,000 in women ages 65-69, which is

126%

higher than the previously reported uncorrected rate22

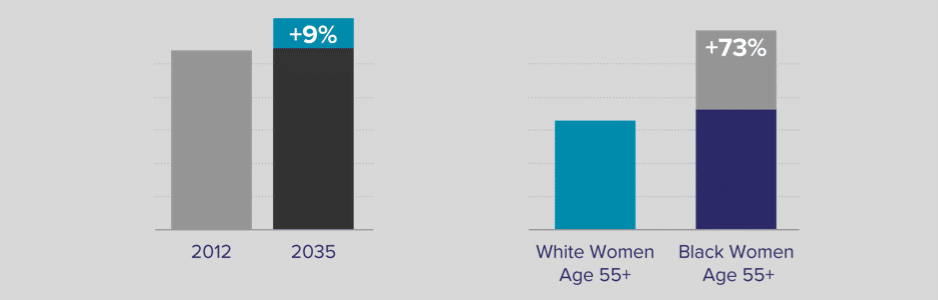

Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer data reveal substantial racial disparities

Fewer women are having hysterectomies, so more will remain at risk for cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer is anticipated to increase by 9% from 2012 to 2035, due in part to an expected decrease in hysterectomies22

If race-related cervical cancer disparities persist, cervical cancer incidence will be 73% higher in Black women compared to White women for ages 55+22

Cervical cancer screening exit criteria23

Screening exit criteria are complex & require a detailed review of at least

10

YEARS OF

MEDICAL

RECORDS

of women ages 64–66 do not fulfill the criteria to discontinue cervical cancer screening

NEARLY

30%

of invasive cervical cancer cases in women older than 65 were diagnosed in women who inappropriately exited screening at age 65

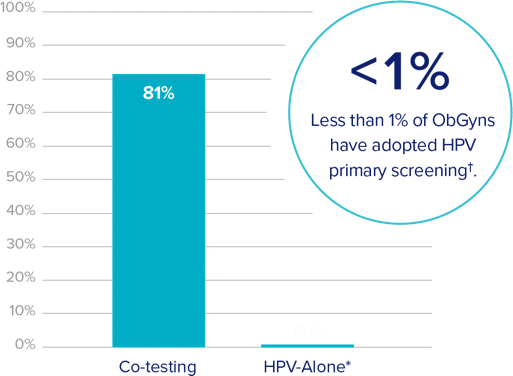

Co-testing adoption rates at an all time high

Remaining 18% is primarily Pap-based testing

†Based on a 2019 survey of ObGyns

ACOG, ASCCP, SGO and USPSTF guidelines recommend:

For women ages 21-29 years:26

Screening with cervical cytology alone every 3 years is recommended.

For women ages 30-65 years old:†26

Co-testing with cervical cytology and high-risk HPV testing every 5 years is recommended.

For women ages 65 years and older:26

Do not require screening after adequate prior negative screening results.

In many cases, co-testing is covered by the Affordable Care Act.

* A positive HPV screening result may lead to further evaluation with cytology and/or colposcopy.

† There are two additional screening methodologies also recommended in this age group. For more information, see the April 2021 ACOG Practice Advisory.